Authors note to paid subscribers: Should you choose to listen to the audio version of this essay, don’t forget to take a look at the end of this written essay where you will find an “in my kitchen, around the farm” update.

Earlier this week, I found myself chatting with a fine lass at a local tattoo parlour. She was the piercer and I, the piercee (I know it’s not a real word, Sir Autocorrect, chill out). Like much else of me, my ears, pierced some forty-two years ago when I was nine years old by an elderly, elegant lady at the Hudson’s Bay jewellery counter, decided that they had enough during covid lockdowns. My poor little ear holes just packed up and headed out for greener pastures.

My piercer was telling me that she’s been quite busy and expects to be even busier in the coming weeks. When I asked what causes rushes in piercings, she told me that it was the soldiers from the military base, just down the road from where we were. “Oh yeah”, she said, “I just got a call this morning from a guy who told me he had to take out his “industrial” piercing fifteen years ago when he got in the military and now that they’re changing the rules, he is finally getting to put it back in.”

I was astounded. The military is allowing piercings? That too? It was only earlier in the week that my husband had heard through a still-serving friend that Canada’s top brass had now wildly rewritten the dress and decorum regulations for service members. Gone are short, tidy haircuts for men and tight, perfectly manicured hair-buns for long haired women. Face tattoos are now okay so long as they don’t say or depict anything that would fall into the “hate content” genre. Along with their long hair, men can also wear any type of facial hair they want. No more shaving every day and “high and tight” haircuts. The parts of regulations that involve not putting your hands in your pockets or chewing gum or holding hands in uniform have also been removed. Earrings can dangle. Nails can be long. Hair can be fuchsia pink, in any sex.

Another wonderfully progressive addition in the military dress regulations, or is it a subtraction, involved de-gendering clothing. No, that doesn’t mean they have gotten rid of the purses and skirts in dress uniforms, it means that men may choose to wear them. They wrote it as if it’s all gender neutral, but the truth is, women could always opt to wear pants instead of skirts so the only difference now is that men can dress as women.

In other words, soldiers have been liberated from the constraints of conforming. Yes, yes, there’s still the whole bugaboo around uniforms in general, but now there’s individual expression and allowances around how clothing is worn. This is a new military, one that has brought in critical race theory (CRT) and antiracism to address the “systemic racism” that pervades its every tank and trolly. Soldiers sit through hours of forced indoctrination, just as they always have, only this is about making them see their role in oppression and how to sniff out the slightest waft of racism from the comrades in their midst. And to help them along the way, the military has installed CRT guides into the pastor/minister positions in bases across Canada.

I wonder if the full length mirrors in the mess halls, the ones with “check yourself” written across the top have been removed. Because, what exactly are you checking yourself for? How pretty or handsome you look? If your nose ring is free and clear of debris?

Say what you will about the military machine. I’d happily join in with you there. But we’re missing something when we don’t understand what the military offers to someone who, like me, found myself applying at the ripe old age of seventeen. I was living alone at a young age and, having been kicked out of school and my home a few times over, I had little options. I worked nights at a truck stop one summer. I had the typical fast food job, flipping burgers, for a bit. But when my mother suggested I join the army, out of exasperation I’m sure, my immediate thought was that I didn’t have what it took to do something like that. It was too hard. I wasn’t good enough, physically fit enough. I had no discipline, just ask my teachers or my principal who told me graduation wasn’t a possibility for me.

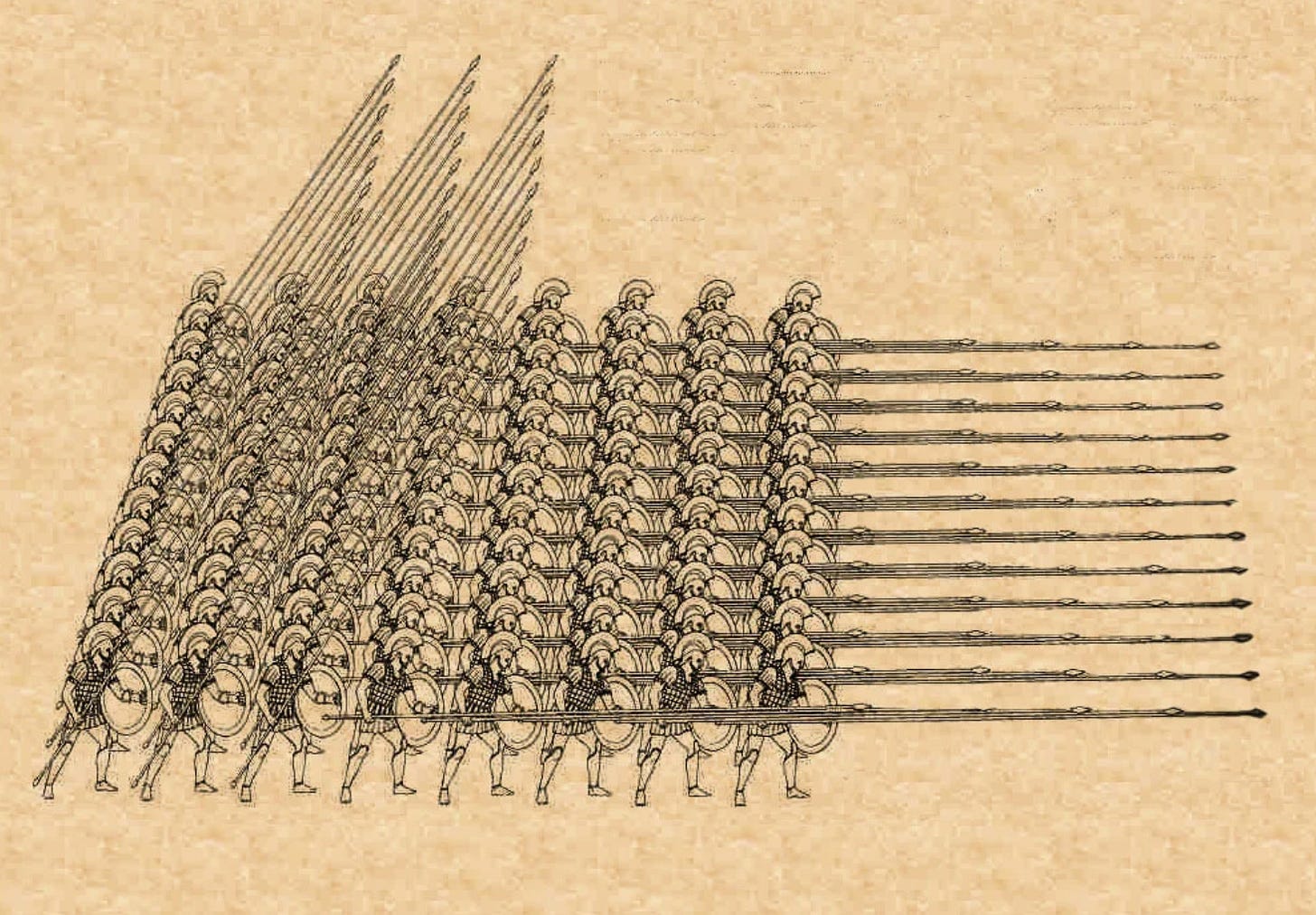

But there was something there. Some sort of flicker of possibility. In those days, university was reserved for those with very high grades. Those who didn’t have them, or didn’t aspire to the jobs a degree would bring, went off to college or trade schools. I didn’t even finish high school so I certainly didn’t have much in the way of aspirations towards anything beyond. I went to an open house night at our local armoury. Instead of the 6’4” mountainous towers of muscle with chiseled jaw soldiers I expected to greet me with a scoff, I was greeted by friendly enough soldiers. We walked about in an orderly mass, all of us “civilians” getting peeks into a foreign land with strange human like creatures displaying odd customs like saluting and forming themselves into measured lines and rows.

None of that interested me or impressed me much. What I was amazed by was the clear parameters of hierarchy and respect I saw. It was a curiosity. Why did a mark on a lapel warrant more respect than another? Everyone had boots shined to a gloss and uniforms crisp and tight. They walked with their backs straight and strong. Men, just a little older than me, answered questions with “Yes, Sergeant!” I felt a little embarrassed even witnessing it. The women had their hair pulled back so tight the corners of their eyes stretched in resistance. Not a single strand out of place. They too, moved about, spoke with confidence, wore the same uniform as the men, and walked with that same sense of purpose.

I didn’t know what that was then, but I wanted some.

I know what that was now. I know because I ended up serving in the military after going through the hell that is boot camp. As a raw recruit, I stood at rigid attention at 0500 hrs every morning, waiting for my Sergeant or Captain to work his way down the row of us until he came to me and stood inches from my face examining every little nook and cranny of my body, of my uniform, and my cubicle which included a bed and a locker. I steeled myself to look right through him at the wall beyond. Every hair was examined, every piece of clothing I wore. My nails and my boots. My collar and my laces. He would move around me looking to find that one little thread I didn’t burn off from a wayward seam or the edge of my combat pants escaping from the boot bands that held them tight against my calves. If all else failed, a piece of lint dangling from the wool of my bed was justification for him to rip it apart.

Every morning there would be something. There had to be something. If it wasn’t on me, it was in my cubicle where my bed was made so tight you could bounce a quarter off it. My locker, with its contents arranged with a ruler, was also full of possibilities of failure. And fail I did. Every morning. That is the name of the game. For weeks, I failed. We all did. We were the dregs, sloppy and hopeless. Mama’s forgotten children. Every morning our leaders inspected and every morning we found ourselves on the linoleum floor doing push ups in recompense.

I can still vividly remember the first time my Sergeant walked up to me and said, “Nice turnout, Couture. Good bun.” Sounds a bit trivial maybe, but that first little drip of you-did-something-a-little-right-here, still evokes a rush of pride in my guts. I know how hard I worked, I perfected, I diligently poured myself into my tasks to earn that praise. I knew it was hard earned, yes, but I also knew it was genuine. I deserved it. I worked for it. It meant something.

And so it went, for years. I, a girl that grew up without any type of sport participation outside of school gym class or outdoor play, discovered that my body was strong and capable. In the military, I placed in the top of all of my classes and courses. I was awarded a commendation for physical fitness. I, for the first time in my life, felt like I could be more. Parts of who I was that lay dormant were liberated. And those parts of me, stagnant and hidden, only bubbled up through the alchemy of discipline and structure. A discipline that was imposed initially, but adopted soon enough. Even if I didn’t see what I was capable of, even if I thought what was being demanded was beyond me, someone else knew it was in there. There was an expectation of me. A demand of me. A standard. And somehow I met it. Again and again.

Of course, this is the military we’re talking about, not the totality of life. The military was shaping us into what they needed from us. Soldiers, pieces of a whole. But it was in that whole that I, and many, many others like me, were able to find something we couldn’t in “the real world”. I didn’t need to know what I was doing or where I was going in life. I just needed to be lined up at 0600 hrs for physical training and run and heave my way as good as the next guy. I didn’t need to know what I was going to do to get my grade twelve diploma finished, I just needed to be where I was supposed to be, looking sharp, and ready to work my tail off. And I did.

Break them down, build them up. Even when you knew that’s what they were doing, it worked. It works because the things that are getting built up on the outside, the soldiering qualities, pale in comparison to what is being built up on the inside.

I can still fondly remember the people I found myself thrown into platoons or units with. My fellow soldiers, there for their own reasons too. There were Newfies with their hilarious sayings and generally lighthearted way of making even the most treacherous tasks seem fun. There were the athletes that struggled to learn to work as a team and were constantly chastised with the biggest of insults from the higher ups, “What do you think you’re an individual?!” Ouch, that one cut deep. “No, Sergeant!” There were the uncoordinated and the physically weak, pushed into physical competence by shame. Hard and fast repercussions found every morning, at every physical training session. For the weak, the rest of us did extra pushups or ran extra kilometres as we double-backed on our runs, again and again, to pull the stragglers back into the fold. On weekends, while we rested, it was common to see those same “stragglers” pushing themselves with extra runs and gym sessions, determined to avoid the ongoing humiliation.

There were the tough guys and gals, those that came from poverty and abuse, that worked harder, it seemed to me, than anybody else. They thrived in that environment. At last, for the first time in their lives, understanding a system. Order. Answers. Structure. A formula where once there was chaos. With discipline comes reward. There were slobs whose uniforms and rooms ladened us all with their laziness. When they were inspected, they didn’t get flack. We did - the collective pays. “Get your fellow soldier together!” We did pushups while he/she stood red faced. Were we mad? Heck, yes, we were mad, just as designed. From then on out, we prepared ourselves for inspection and then headed to the troublesome soldier to square them away. We were impatient and disgusted and our fellow soldier was embarrassed. We, the society in this world, expected more and the sloppy soldier, the target of our dismay, had two choices: rise up or be shunned. And you know, almost always, they rose up. Either that or they were done. But when they did, their pride replaced their shame. And that’s a lesson too oft missing in today’s world.

The officers were the smart ones. The ones with the degrees that ruled from on high. We were not that. And so, they passed down their orders while our leaders, raised up from the lowly ranks like us, directed. Our Master Corporals and Sergeants and Warrant Officers knew us and, the best of them, would pull from us what needed to be pulled and pushed us in ways that challenged our weaknesses. Always, in everything, you can be better than this. You can do better than this.

That never leaves you. At least, it’s never left me. They’re too good, those master brainwashers. It was too masterful, that implantation into my brain. I can’t even make out the edges anymore. I can be better than this. I don’t know how or what it takes to get me there, but I am a wellspring of untapped potential. That is what I left the military with. I went in a lost young girl with no direction. I left knowing that the life I was returning to had answers and direction and I was capable of taking all of it on.

Huh. Me, capable. Who woulda’ thunk it.

Isn’t that what the great gift of challenges and hardships are all about? There is no teacher or guru capable of giving you what life’s hardest moments can. Sure, there are words and platitudes and lessons to read about, but it is only through actually living through something that we are shown what stuff we’re actually made of. That was the gift the military gave me. In hindsight, I’m not sure I could have ever learned those things about myself, given the me I was. I had no idea that what I was doing when I stood at attention on black asphalt for hours on end, skin blistered by the sweltering sun, had anything to do with discovering who I was or what I was capable of. My determination and grit. I didn’t have determination and grit going in. All I knew was that I was lazy and hopeless and yet, there I was on that asphalt standing still and turning and slamming my foot down at the bark of a Sergeant in front of me. Dumb and meaningless suffering, that’s what I was thinking then.

Wax on. Wax off. Left turn. Right turn.

Nothing in this world could have changed my perception of self other than moving through the darkest of cavernous hellholes and coming out the other end. It remains that way still as I continue to evolve and grow. I’m a stubborn sort. Through the hellholes we go. Forward ho! There was no therapist or kind confidante that was going to find the words that would pull me through to the other side. No, some paths need fire and brimstone.

But we’ve changed our bent in this brave new world. The institutions that once held us to something greater are fading under ideologies that purport to usher in a new era of inclusivity and equality for all. Children’s sports teams assert that winners and losers are damaging and so there will be no score counting. Work as hard or as little as you like, we’re all winners here. Universities have dramatically lowered entrance standards. Today, most kids can get into some sort of university and thus, degrees have become quite meaningless. Cashiers at the health food store and uber drivers are full of university qualified humans all struggling to pay off their student debt. Fire departments and police too, have watered down expectations. It’s everywhere, yes, but what you lose when you apply these principles to the military wounds me personally.

Who joins the military as an enlisted man? Oh, oops, enlisted person? Is it still enlisted? Pundits and experts from around this country have weighed in with their opinions on why the military is bleeding, more aptly hemorrhaging, personnel. Get rid of the archaic ideas, they say. “Nobody wants to work in an old, tired, organization that draws its culture and values from a museum, people want to be part of an agile organization that rewards modern values.” Really? You sure? Because I don’t see that at all.

Yes, there are the ideologues that call for, and have well succeeded as I’ve already mentioned, in bringing far-left ideologies into the framework of our military, but these are mainly people at the top setting the cadence for the people below them. And those people at the top are products themselves of these far-left ideologies that have completely infiltrated and saturated our institutions of “higher learning”. And so, where they go, so go these ways of looking at the world. But, the very gears that make a military work are drawn from segments of the population who are a little closer to the realities of life. The blue collar workers. The folks that understand that ideas are all well and good, but there is a real world where real work calls for brushing away of ideologies. Those ideas don’t work on the ground and nobody likes to have values shoved down their throats.

I like to think that I have a pretty good looking glass to peek into the minds and motivations of younger people today. Yes, there are the parrots squawking radical notions on repeat. Let’s leave those to the side while they figure things out in life. It’s the others, the young women I know through my grown daughters and the others I have had the pleasure of meeting and speaking with through my writing. They are tired of the unstructured, anything goes, promiscuity and excesses of their time. Young women wondering if the men around them will ever rise up and expect anything more than a one night stand. And young men, told their worth is in their compliance to a woman, in the softening of their masculinity, in how many dollars they earn. It’s everyone for themselves, no rules. Just keep your judgments to yourself and repeat the mantras as given.

Do I think these young people would join the “new” military en masse? Of course not. I don’t think they should either. Why would they? For more of the same with crappy pay and the abject disrespect and devaluing from their higher ups? To grind yourself for an institution that now also thinks it’s within their purview to fill your mind with their political bent? For the weakened camaraderie and morale that comes from these ideologies that are determined to highlight our differences and magnify our, supposedly well-needed, shame? Why would I ever tell someone to join such a place? I wouldn’t. Don’t do it. Everything that was good is gone.

A young, strapping lad that lives near us once expressed to me his desire to join the military. He’s a farm boy, always working hard on some side hustle. He fells, bucks, splits, and delivers firewood. He clears driveways of snow in the winter. He cuts lawns in the summer. He did well enough in high school but he’s itching for something more. Always, he’s good natured and funny. He was liked by all on his hockey team, a good team player. But he wants out of this little country life. For now. He’s like a coiled spring ready to pop. Decades ago, I would have said something different to him, but now I tell him, “No, don’t do it. The military is not what it was. You’ll hate it. You’re too good for them.”

This is what happens when our institutions start to disintegrate. Those decision makers at the top of the hierarchy are making decisions that would appeal to a group of people that would never join the military in the first place. Those entrenched university students, savvy with the lingo and the ideas of critical race theory, are never going to join the army as a soldier. And the young people that would are baffled by this new military that has replaced pride with equality. They’ve confused expression and inclusivity with values and their right to determine them. These ideologies insist. They offer nothing. It’s a slippery, shadowy, insidious decline of expectations. Purple hair with face tattoos and men with long hair wearing women’s skirts, yes. But don’t you dare utter a word of wrong-speak.

It’s the “soft bigotry of low expectations” showing up. Again.

Here’s a thought: what if tradition and high standards are exactly what’s missing from what the world offers our young right now? What if the very things that make the sacrifice of military service worth it are now being erased? Has anyone asked the rank and file if critical race theory training and men wearing skirts will keep them around longer? Has anyone bothered to look at retention? They weren’t doing that three decades ago when I served. They had a “this is what you get, take it or leave it approach”. Seems that’s remained, only the what you get part of the equation has dwindled. What if the military dropped the idea of competing with the likes of social media companies and other jobs with low standards, and put their focus on what they can offer that very few other institutions can. Kind of like they used to. Pride. Discipline. Camaraderie. Discovering that you are so much more than you realize. It may just turn out that more soldiers, serving with pride and honour, paid well, with some thought to their families and homes would keep more people around. And that would mean less deployments and burdens for those willing to tough it out.

Or we could tell soldiers that their whiteness is a shame to be purified and their masculinity a toxic, ugly thing. Either way…

My husband and I know serving members, ones that have been in the Canadian Armed Forces for decades, career soldiers, who are now counting down their time to retirement. “I’ve never seen morale so bad”, they’ve said. “Every young person I meet who has dreams of joining, I redirect”.

It’s a toxic work environment, filled with suspicion and dread. Not because the work is indescribably tough. Not because they have to present themselves with extreme care, slicked and polished to within an inch of their life. Not because they are chastised when they don’t meet the standards in dress or physical fitness. But because none of this matters anymore.

Thinking back now, to that young girl I was over thirty years ago, I wonder what today’s military would be able to offer me. Had I gone into that armoury and found women walking around with painted long nails and flowing blue hair or men with long hair and face stubble slumping about, I don’t know if I would have understood that place to be any different than what I knew. Where is that pride that was always drilled into us back in the day?

The pay, the benefits and the deployments have only worsened as the mass exodus continues. And as people leave, those left behind are demanded to do more to patch the holes. Families suffer as a result. The glue that kept it all together, the stuff that offered, in return for the hellish conditions, something far greater than most could get anywhere else is now going or gone all together. We’ve traded honour and tradition, virtues that build, for untested ideologies that erode and degrade. Will what’s on offer be enough in trade for the call of sacrificing one’s life for their country? Either way, it appears for now that the weakening of our fundamental structures marches on. Almost like it’s by design or something.

in my kitchen, around the farm

This week has been all about snow. My daughter and I ended up getting caught in a total white-out blizzard, driving home from a trip we had to take into town. One of the perils of never listening to, or reading, the news is that the weather is always a